Let’s take Apple’s Siri as an example: Siri launched with only English, then soon after added support for French, German and Japanese. More have since been added, but if this is a computer picking up the sounds we make and converting them into words then why can’t it simply work with a lookup dictionary in every language?

Or to put it another way, if Siri can turn speech into words that it recognises, why can’t Siri be provided with an all-encompassing, global dictionary and recognise all words?

The answer lies in the predictably of how we speak.

It’s all about the phonemes

Once your choice of voice recognition software has recorded your voice, the next step is to convert this audio into a series of phonemes. A phoneme is the smallest unit that a language can be broken down into and they’re simply the sound that a letter or combination of letters makes when spoken together. For example, the ch in church is a phoneme and the c in curl is a different phoneme. US English has 40 of them. Obviously each language has its own, though some will overlap.

So the first hurdle is: how well do you speak? How well do you meet Siri’s expectations?

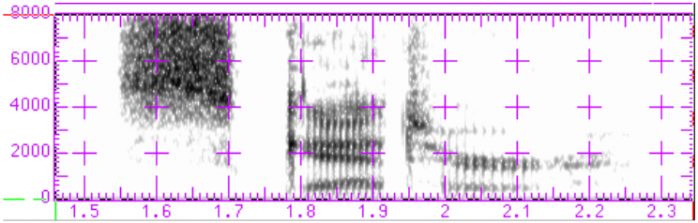

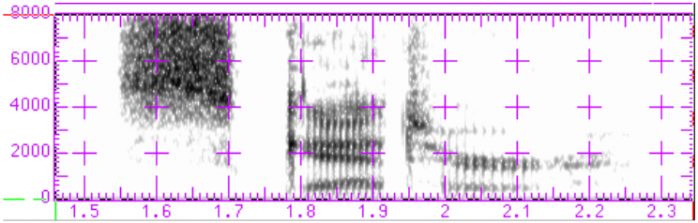

I won’t go into the details of how voice recognition works and I don’t want to get bogged down in how it predicts which of the similar-sounding words you intended. Suffice to say when Siri is looking for one of 40 phonemes, even allowing for your particular pronunciation, it might hear something different. Some people speak faster than others and appear to merge phonemes, some languages allow a degree of lenition, some languages or accents render flat vowels as diphthongs and vice versa, not to mention background noise and the occasional drunken slurring into the microphone. But while the software has been provided with a frequencies-to-phonemes voice map (the image at the top of this article is a visual representation of the word “said”), how can it be expected to handle regional phenomena such as glottal stops or plosives, fricatives or affricatives, nasals or semi-vowels?

Keep It Simple, Stupid

The ‘model’ that the software is supplied with is an aggregated model and a margin of error is tolerated, but some languages will deviate from this more than others. In short, the lesser the distance between phonemes, the more difficult the recognition of that language, not just for recognition software but also for human learners. In addition to pronunciation obscuring the phonemes, the duration of a word also plays a part: longer words give the software more of a chance, shorter words less so. And again, some languages lean towards shorter words, thus asking more of the software.

So to readdress the question, “Why can’t Siri understand all languages?”, if we all spoke robotically the same, regardless of language, then perhaps Siri could. Then again, who would want that?

Cover picture: A spectograph of the spoken word “said”, obtained from here.