Every sport has its own peculiarities, and the longer a sport has been around, the more chances it has to accumulate a maze of specialist terms that can leave casual onlookers baffled. (Would you rather have sticky wickets or a maiden over? Why is an albatross better than an eagle?) Tennis has its own share of language quirks, from the sublime (everything David Foster Wallace wrote about the sport) to the ridiculous (the obligatory head-scratching about what to rename Henman Hill whenever a new British player starts doing well at Wimbledon). One of its biggest quirks, however, is the scoring, which is a morass of seemingly arbitrary numbers and terms. So where do we get love and deuce from?

What the deuce?

Unlike the straightforward scoring systems used by the majority of sports, tennis comes with a scoreboard full of arcane choices. The origins of 15, 30, 40 are unknown, though it may be related to the quarters of a clock face. And why not 45? It may simply be because 40 is easier to say than 45, or because a player needs two points to win, so moving to 40 on this metaphorical clock face allows it to move to 50 at deuce, and then 60 for the win.

Which brings us to deuce. This one probably stems from the French deux, or two, because from deuce you need two points to win. From there it moves to the linguistically obvious ‘advantage’ (though less obvious is why it moves away from numbers entirely). Which leaves just one more score…

The language of love

Why is love the term for zero in tennis? It’s one of the most enduring puzzles in the game. The most popular theory is that it’s French again: a zero is egg-shaped, and the French word for egg, l’oeuf, sounds like love when mangled by an English speaker. (The French themselves simply use zero.)

There are other theories, of course. It may relate to the Dutch word lof, meaning honor, distinguishing those who played for monetary rewards from those simply playing for honor. Which is pretty similar to another theory – that players who repeatedly end up scoring nothing can only be playing for the love of the game.

Keep it short and sweet

Tennis scoring has remained surprisingly unchanged over the years – occasional attempts to switch to a sensible system of 1, 2, 3 have been resoundingly rebuffed. It’s left to individual players to add to the sport’s impenetrability. Few go as far as the Bryan brothers, identical twins who are the most successful doubles players of all time and use their own language on court, but you often hear plenty of non-standard phrases – from five (shortened from fifteen, which obviously takes exhausted players far too much effort to say), to van in and van out (advantage to the server or receiver, respectively). Though after a few too many of those, the players presumably want to hear nothing but game, set and match.

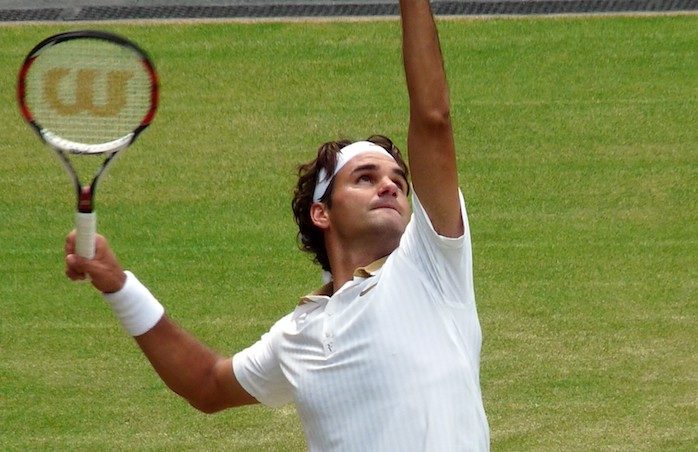

Title image via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)